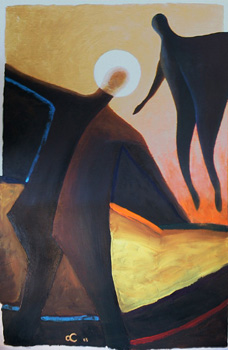

Tempted

Original Article Posted on Journey With Jesus Webzine

Used with Permission and Much Gratitude

By Debie Thomas. Posted 23 February 2020.

By Debie Thomas. Posted 23 February 2020.

For Sunday March 1, 2020

Lectionary Readings (Revised Common Lectionary, Year A)

Genesis 2:15-17, 3, 1-7

Psalm 32

Romans 5:12-19

Matthew 4:1-11

On this first Sunday in Lent, we follow Jesus into the wilderness, and watch as the Son of God confronts the fullness of his humanity. As Matthew’s Gospel describes him, Jesus is “famished” after forty days of fasting. Physically, he’s at the end of his strength. Socially, he’s alone and friendless. Spiritually, he is struggling to hang onto his identity as the glow of his baptism recedes into a hazy, pre-wilderness past. And it’s in this state of vulnerability that the tempter comes, ready to pull Jesus away from his belovedness, and his vocation.

Yet it is precisely the appalling messiness of humanity — both Jesus’ and our own — that we grapple with during Lent. We begin on Ash Wednesday, acknowledging via the imposition of ashes that we will surely die, that our bodies will fail us no matter how cleverly we attempt to preserve them with medicine, exercise, cosmetics, or mindfulness. Â

From that austere beginning, we venture into the wilderness like Elijah, like Moses, like the Israelites after their exodus from Egypt. With ashes on our foreheads and mortality on our minds, we begin a precarious journey inward, a journey to explore who Jesus is, who we are, and what our shared humanity requires of us here and now.

As Matthew tells the story, the devil comes to Jesus in the guise of a brilliant interrogator.  “Can you be like God?” is the savvy question he posed to Adam and Eve in the lushness of the first garden. “Can you take hold of a higher wisdom, a keener knowledge, a more divine humanity?” Â

As Matthew tells the story, the devil comes to Jesus in the guise of a brilliant interrogator.  “Can you be like God?” is the savvy question he posed to Adam and Eve in the lushness of the first garden. “Can you take hold of a higher wisdom, a keener knowledge, a more divine humanity?” Â

Now he comes to the exhausted Son of God with a shrewd inversion of those primordial questions: “Can you be fully human? Can you abdicate power? Exercise restraint? Work in obscurity? Can you bear the vulnerability of what it means to be weak and mortal and human?”

I have to confess that until fairly recently, I didn’t see what the big deal is with the devil’s taunts. Jesus is starving, after all. Who cares if he zaps a rock or two into bread?  God is supposed to be Jesus’ protector after all, an omnipotent commander of legions of angels. Why is it sinful for a son to call on the protection of his father? Jesus is the rightful ruler of all the earth’s kingdoms, after all. What’s wrong with him receiving the worship that’s his due?Â

These days, I read the story differently.  The devil doesn’t come to make Jesus do something “bad.”  He comes to make Jesus do what seems entirely reasonable and good — but for all the wrong reasons.  The test is a test of Jesus’s motivations.  A test of his willingness to identify as fully human, even as he is fully God.

The first temptation targets Jesus’s hunger.  “If you are the Son of God, command this stone to become a loaf of bread.”  The temptation implies that God’s beloved should not hunger.  In the devil’s economy, unmet desire is an aberration, not an integral part of what it means to be human.  In inviting Jesus to magically sate his hunger, the devil invites Jesus to deny the reality of the incarnation.  To “cheat” his way to satisfaction, instead of waiting, paying attention to his hunger, and leaning into God for lasting fulfillment. Â

Along the way, the devil encourages Jesus to disrespect and manipulate creation for his own satisfaction.  To turn what is not meant to be eaten — a stone — into an object he can exploit. As if the stone has no intrinsic value, beauty, or goodness, apart from Jesus’s ability to possess and consume it.

Many of us have “given up” something for Lent this year.  Chocolate, wine, TV, Facebook.  The goal is to sit with our hungers, our wants, our desires — and learn what they have to teach us.  What is the hunger beneath the hunger?  Can we hunger and still live?  Desire and still flourish?  Lack and still live generously, without exploiting the beauty and abundance all around us?  Who and where is God when we are famished for whatever it is we long for?  Friendship, meaning, intimacy, purpose?  A home, a savings account, a child, a family?

I write these words with trepidation, because I know what it is to let hunger gnarl and embitter me.  Hunger in and of itself is not a virtue, it’s a classroom.  To sit patiently with desire — to become its student —  and still embrace my identity as God’s beloved, is hard.  It’s very, very hard.  But this is the invitation.  We can be loved and hungry at the same time.  We can hope and hurt at the same time.  Most of all, we can trust that when God nourishes us, it won’t be by magic. It won’t be manipulative and disrespectful.  It won’t necessarily be the food we’d choose for ourselves, but it will feed us, nevertheless.  And through us — if we will learn to share — it will feed the world.

I write these words with trepidation, because I know what it is to let hunger gnarl and embitter me.  Hunger in and of itself is not a virtue, it’s a classroom.  To sit patiently with desire — to become its student —  and still embrace my identity as God’s beloved, is hard.  It’s very, very hard.  But this is the invitation.  We can be loved and hungry at the same time.  We can hope and hurt at the same time.  Most of all, we can trust that when God nourishes us, it won’t be by magic. It won’t be manipulative and disrespectful.  It won’t necessarily be the food we’d choose for ourselves, but it will feed us, nevertheless.  And through us — if we will learn to share — it will feed the world.

The second temptation targets Jesus’s vulnerability.  “[God] will command his angels concerning you,” the devil promises Jesus.  “On their hands they will bear you up, so that you will not dash your foot against a stone.”  The implication is that if we are beloved of God, then God will keep us safe.  Safe from physical and emotional harm, safe from frailty and disease, safe from accidents, safe from death. Â

It’s such an enticing lie, because it targets our deepest fears about what it means to be human in a broken, dangerous world.  We want so much — so much — to believe that we can leverage our belovedness into an impenetrable shield.  That we can get God to guarantee us swift and perfect rescues if we just believe hard enough.  But no. If the cross teaches us anything, it teaches us that God’s precious children still bleed, still ache, still die. We are loved in our vulnerability.  Not out of it.

The third temptation targets Jesus’s ego.  After showing Jesus “all the kingdoms of the world,” the devil promises him glory and authority.  “It will all be yours,” the devil says.  Fame.  Visibility. Recognition.  Clout.  A kingdom to end all kingdoms, here and now.  The implication is that God’s beloved need not labor in obscurity.  To be God’s child is to be center stage: visible, applauded, admired, and envied.  A God who really loves us will never “abandon” us to a modest life, lived in what the world considers insignificance.

That Christians tend to have an uneasy relationship with power is an understatement.  Church history is littered with the ugly fallout of “Christian” ambition, power, fame, and authority gone awry.  So the question for us is whether we can embrace Jesus’s version of significance, a significance borne of humility and surrender.  How important is it to us that we’re noticed?  Praised?  Liked?  Is our belief in God’s love contingent on a definition of success that doesn’t come from God at all?  Can we trust that God sees us even when the powers-that-be do not?  Can our lives as God’s beloved ones thrive in quiet places?  Secret places?  Humble places?

The uncomfortable truth about authentic Christian power is that it resides in weakness.  Jesus is lifted up — but he’s lifted up on a cross. Â

Three temptations. Â Three invitations. Â What will we do with them?

If Jesus’s forty days in the wilderness is a time of self-creation, a time for Jesus to decide who he is and how he will live out his calling, then consider carefully what the Son of God chooses: deprivation over ease.   Vulnerability over rescue. Obscurity over honor. At every instance in which he can reach for the certain, the extraordinary, and the miraculous, he reaches instead for the precarious, the quiet, and the mundane.   Â

If Jesus’s forty days in the wilderness is a time of self-creation, a time for Jesus to decide who he is and how he will live out his calling, then consider carefully what the Son of God chooses: deprivation over ease.   Vulnerability over rescue. Obscurity over honor. At every instance in which he can reach for the certain, the extraordinary, and the miraculous, he reaches instead for the precarious, the quiet, and the mundane.   Â

Needless to say, there’s nothing easy about affirming Jesus’ choices.  Sometimes I find them appalling.  I much prefer the miraculous intervention, the dramatic rescue, the long-awaited vindication.   I understand too well the demands of the tempter: Feed me! Deliver me! Prove yourself to me!   I know what it’s like to find the restraint of God offensive.Â

The other aspect of the temptation story we might consider offensive is this: God’s Spirit orchestrates it.  Jesus doesn’t meander into the wilderness on his own. He doesn’t schedule a National Geographic expedition, or a marathon in the desert to rack up Fitbit steps. According to Matthew’s Gospel, the Spirit leads Jesus into the wilderness, specifically “to be tempted by the devil.”

I’ll admit it: I don’t know what to do with the Spirit’s role in this story.  But might it be possible to draw some comfort from it?  Simply because it rings true — that even the wilderness can’t separate us from God’s purpose and care?  After all, we don’t choose to enter the wilderness, either.  We don’t (for the most part) volunteer for pain, loss, danger, or terror. But the wilderness still happens.  Whether it comes to us in the guise of a hospital waiting room, a toxic relationship, a troubled child, a sudden death, or an unshakeable depression, the wilderness appears, unbidden and unwelcome, and sometimes we have no choice but to trek into its barrenness.  Sometimes — can we bear to ponder this? — it is God’s own Spirit who drives us into the parched landscape amidst the wild beasts. Â

Does this mean that God wills bad things to happen to us? That he wants us to suffer? I don’t think so.  Does it mean that God can redeem even the most desolate periods of our lives? That our deserts can become holy even as they remain dangerous? Yes. I believe so.

I write these lines hesitantly, too aware of how Christians have suffered under the false teaching that God authors human pain and suffering for some greater good of his own devising.  God does not. But we walk a fine line, nevertheless. Sometimes our journeys with God include dark places. Not because God takes pleasure in our pain, but because we live in a fragile, broken world that includes deserts, and because God’s modus operandi is to take the things of death, and wring from them resurrection.

At his baptism, Jesus hears the absolute truth about who he is.  The Beloved.  That’s the easy part. The much harder part comes in the wilderness, when he has to face down every vicious assault on that truth. When the memory of his Father’s voice from heaven fades, and he has to learn how to be God’s beloved in a lonely wasteland. Â

At his baptism, Jesus hears the absolute truth about who he is.  The Beloved.  That’s the easy part. The much harder part comes in the wilderness, when he has to face down every vicious assault on that truth. When the memory of his Father’s voice from heaven fades, and he has to learn how to be God’s beloved in a lonely wasteland. Â

Maybe we, like Jesus, need long stints in the wilderness to learn what it means to be God’s precious children.  Because the unnerving fact is this: we can be beloved and uncomfortable at the same time. We can be beloved and unsafe at the same time. In the wilderness, the love that survives is flinty, not soft.  Salvific, not sentimental.  Learning to trust it takes time.  Â

So.  What does Jesus’s temptation story mean for us as we begin our Lenten journeys this year?  Maybe it means we need to follow Jesus into the desert.  Maybe it means we should hunker down and look evil in the face.  Maybe it’s time to hear evil’s voice, recognize its allure, and confess its appeal.  Maybe it’s time to decide who we are and whose we are. Â

Remember, Lent is not a time to do penance for being human.  It’s a time to embrace all that it means to be human.  Human and hungry.  Human and vulnerable.  Human and beloved. Â

May the God who loves us even in the wilderness, grant us a holy Lent.

Debie Thomas:Â debie.thomas1@gmail.com

Image credits: (1)Â Wikimedia.org; (2)Â Chris Cook Art; (3)Â Catholic World Report; and (4)Â Wikimedia.org.