When Matt Became Jade

Many at Northern Secondary School were surprised when Matt H. announced last year that he was running for student council president. A somewhat lonely boy, he didn’t fit the model of the popular, extroverted student leader. Everyone seemed to know the outgoing president. Matt was more reserved – he liked playing on-line games and writing. He was on the ninth revision of a fantasy novel.

Many at Northern Secondary School were surprised when Matt H. announced last year that he was running for student council president. A somewhat lonely boy, he didn’t fit the model of the popular, extroverted student leader. Everyone seemed to know the outgoing president. Matt was more reserved – he liked playing on-line games and writing. He was on the ninth revision of a fantasy novel.

Everyone told him he didn’t have a hope of winning. But he got the signatures needed for a nomination. For his election campaign that spring, he made a funny video, an instant teenage classic that showed him drinking a smoothie made from everything in his refrigerator. On stage at an assembly, where he stood tall, at 6 foot, 4 inches, wearing a Hawaiian shirt, he made a short satirical speech that parodied campaign promises: “I’ll prevent a gigantic meteor from crashing into the school,” he boasted. He won a standing ovation. It was a narrow margin – 16 votes – but he won the election.

In December, just seven months later, students and teachers saw an entirely different school president. The acting principal, Tony Kerins, sent teachers a letter saying that Matt had made a “gender presentation decision” and would soon be dressing as a girl at school. For the rest of the year, Matt would be known as Jade.

The staff wasn’t asked to prepare students. The thinking was that Jade should not be seen as an exhibit and exposed to an open forum about her change. “We have this person who is one of us,” Kerins said, “and we are not going to have that person hurt or embarrassed.”

Just before the Christmas break, Jade chose her outfit for her first school day as a girl – a ruffled knee-length black skirt, pink T-shirt and black jacket and a dark wig that flipped up at the ends. The next day, she began life as Jade.

She was escorted to her classes by Dale Callender, a counsellor from Delisle Youth Services, a dropout-prevention centre at the school that’s expanded into many parts of student life. Callender, a neat, compact man, in his mid-30s, is a respected figure, immersed in school culture – he’s like an icon here, one student said – and there’s usually a gaggle of teenagers waiting outside his third-floor office.

He stayed by Jade’s side all day, to answer questions from other students and to convey subtly, but firmly, that no nonsense would be tolerated. He and Jade heard a few snickers and saw some startled looks. But that was all. The curious ones came to Callender later with their questions: Is this for real? Why is he doing this? Is he gay?

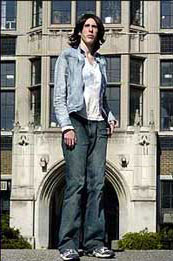

Meeting Jade for the first time requires a moment’s adjustment. She’s wearing a skirt and size 13 runners, and her legs are long. She has a low speaking voice. “I don’t have female mannerisms,” she says, sitting in Northern’s student-council office, a room with a wrecked-basement quality to it. “The way you stand, the way you walk, the way you use your hands. I have to learn that. It’s interesting.”

The questions kids asked Callender were ones Matt had asked himself in the year or two before he became Jade. He had known for a long time that something was awry. He’d secretly tried on his mother’s skirts when he was 6. He confided to a friend once that he wondered about his sexual orientation, though he knew he wasn’t attracted to boys.

A year ago, as school ended, instead of looking forward to the idle days of a teenage summer, he was beset by panic attacks. He’d had them over the years, but now the intensity seemed overwhelming, and it was increasingly clear what was causing them. He disliked his name. He resented being referred to as “him”. Deep down, Jade says, “I always knew I wasn’t male. I’d pretty much ignored it until I was 17 and the stress kept building and building.”

As a child, Jade was shy, and highly observant. “Though my upbringing wasn’t strict, I was careful not to break rules,” she says. “I was afraid of offending anyone. I didn’t want to be a burden. I found it difficult to swear.”

Her father, Michael, is a labour lawyer, her mother, Anne, a humour writer and novelist who’s working on a theology degree. Anne came out as a lesbian when Matt was in Grade 7. The couple’s divorce was peaceful and Mike lives a block away from Anne and their two children.

Other kids found Matt a little eccentric. But he made a few enduring friendships. One such friend was Ben McNelly. As children they played with their action figures and video games and created villages and stories around their action figures in Matt’s room. “Jade was nice to me,” says McNelly, who’s now the editor of Northern’s student newspaper, Epigram, “and I was nice to her. She was refreshing. With some kids you’d play with action figures and fight. I felt more imaginative when I was around her. She has such a wonderful imagination and she brought that out in me.”

In mid-summer Matt called Dale Callender to talk about the stress he was feeling. “I’ve never actually felt comfortable in my body. Imagine your mind telling you that this is just wrong.” Under international standards of care, 18 is the minimum age for a sex-change operation. Matt was 17. But he began thinking about coming out at school.

That August, Matt and his mother drove to their family cottage, and conversation turned to some skits at school in which the boys were to play female roles, a la The Kids In The Hall. As they were unloading the car at the cottage, Matt obliquely told Anne what he had in mind. It wasn’t easy. “Though my mother had come out as a lesbian, I found it very uncomfortable to tell her. I only said, ‘That thing we talked about in the car, maybe I’d like to do that.'”

“It took me a while to figure out what she was saying,” Anne says. “I wasn’t hearing any of that ‘I hate living as a male.’ I was hearing ‘I want to wear women’s clothing.’ I thought if she says it, I have to accept it.”

Anne recalled her own fears in telling her children she was gay – she’d hoped they would see the importance of being true to oneself. “This is a kid who has always been self-aware,” she says. “I believe she did this because this is truly who she is. What we wear and how we present ourselves is an expression of who we are.”

The language around the change Jade is making is fluid, and often confusing. “Transgender” is the word Jade uses, and it describes those who feel uncomfortable in the body they were born with. “Trans,” as in trans-teen or trans-youth, is a newer term that includes transgender as well as transsexual – those who want to change gender using hormonal treatment and possibly surgery. “Trans” may also include those who don’t fit either gender and want to present themselves as “trans,” a third identity, neither male nor female.

There are three child and adolescent gender-identity clinics in the world; the only one in North America is at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, where 500 children and 300 teens have been assessed for “gender identity disorder” or “gender dysphoria,” which means unhappiness, since the mid-1970s.

In the past two years, the Toronto clinic has seen a spike in teen referrals. Fifty children and teens are on the waiting list for assessment at CAMH, says Ken Zucker, the psychologist who heads the clinic. Zucker and his colleagues have given a lot of thought to the reasons for the increase. One possibility, they say, is an explosion of interest in the media – many popular televisionseries, from Law and Order to E.R., have included episodes with transgender characters. Young people may also be turning to gender change as a solution to other problems; a girl may think she won’t be bullied if she dresses like a boy. Most controversial, Zucker says, is the effect of non-sexist child-rearing methods. Zucker demurs from this view. “As if raising them in a more diffuse way causes them to be more uncertain about gender,” he says.

Gender identity develops between ages 2 and 4, the result of genetic inheritance, exposure to hormones during fetal development and possibly environmental factors. But the onset of puberty – with its biological changes and development of sexual curiosity – can push children struggling with gender identity into crisis, says Dr. Krista Lemke, a psychiatrist at Whitby Mental Health Centre. “As a younger child your body isn’t clearly that male or female. With clothes on you can present either way.” Suddenly, that changes.

In a world unforgiving of gender ambiguity, suicide attempts, drug use and running away from home are not uncommon when transgender teens don’t have a lot of support. Of the 10 teenagers he’d seen the previous day, Zucker noted, seven had dropped out of school.

Gender is, after all, a fundamental part of identity. We recognize people by their sex; our first descriptions are often of gender – “I met a man on the elevator … A woman I know …” When these neatly organized divisions are upset, our response can be visceral.

Changing such a profound part of one’s being may seem inconceivable to those who haven’t encountered gender identity questions before. That young people choose to change, no matter how frightening it may be, Lemke says, “speaks to how strong that internal sense is.”

Teens deciding to make the transition first do an internal audit, says Steve Solomon, a social worker in the Toronto District School Board’s human sexuality program. “Will it be risky and make me more vulnerable?” he asks. “Will it give me more integrity and a sense of ‘This is who I am,’ a sense of completeness and honesty? They weigh this against risk. If they end up being true to themselves, it’s similar to the way gay and lesbian youth come out. I’ve seen the stress lines go from their faces.”

He’s worked with about a dozen trans-teens who have come out at school, and others who haven’t. “It makes we wonder, for every student I get to meet, how many more keep it to themselves?”

At the end of the summer, Jade decided not to come out at school. Instead, she would dress as a girl at home. Anne went shopping for clothes. She wasn’t sure of Jade’s tastes and didn’t know what was fashionable for teenage girls. Her child didn’t feel at ease trying on girls’ clothing in department stores, so she found a store in Whitby that catered to tall women, though most styles weren’t suitable for teens.

Jade wore those clothes at home for the first few months of school. “Still the stress of being in the closet was too much,” she says. At Halloween she wore a flowery pink cocktail dress to school. “People laughed hysterically. Of course, no one knew then, so they took it as a joke. But I enjoyed it. It was the one day I could cross-dress in public but still be without as much fear as usual of ridicule.”

Anne’s first clue that Jade wanted to live as a woman – not just cross-dress at home – came in a phone call from school in the late fall, asking her to a meeting to discuss Jade’s transition.

“I knew there’d be stress,” Jade says, “but there really wasn’t an alternative for me. I had to live the life I needed to live no matter what that brought.”

By now she was called Jade, a name she had used for a favourite character in her novel – “one of the most misunderstood and underestimated characters in the group.” She’d written down lists of girls’ names, and for a few days used the name Jenn, which she’d always liked; but eventually she discarded it. Jade, she says, just felt right.

They had to move quickly. Jade hadn’t yet told her father, whom she saw once a week for dinner or a movie, though they had very different interests. Mike is athletic and plays football and basketball in a men’s league; he finds little interesting in the culture of technology, which he says creates distances between people. “Jade knew I was distrustful of the thing she loved the most.”

But minutes after Anne told him that Jade was cross-dressing, Mike hurried to see her. He didn’t want Jade to think that he had hesitated for a moment. “In theory I had a choice,” he says. “In reality, it was a no-brainer. There was nothing to do but be completely supportive. It was a turning point.”

He recalls the waves of emotion he felt as the news settled. “My first reaction was sadness and fear for the future, that she was exposing herself to a lifetime of hardship. Life is hard enough.

“My second reaction was sadness for the past. There were many periods of Matt’s childhood when I wondered why Matt wasn’t happier. I was now able to understand that Matt for his whole life felt uncomfortable wearing clothes we’d bought for him.

“My third was admiration. You tell your kids to respect others despite differences … to be themselves and not what other people want them to be. I was proud to have a child who had the courage to do that.”

But what lay ahead? “I wanted to make sure my child was doing this with eyes open, so she understood from an adult perspective what this meant. Was this something you need to do at school, could you pick your times – after school, weekends, social occasions? Beyond high school, there’s university, and beyond university …”

Mike wanted Jade to consider all this. But he never wanted to talk her out of the change. “Here was a child who had wondered, ‘Does my father really support me?’ I realized how important my role was.”

The next time Jade went shopping it was with her father. They went to Take a Walk on the Wild Side, on Gerrard St. E., where a burly man wearing a five o’clock shadow and a miniskirt met them at the door. Jade tried on clothes, including a brassiere and breast forms, and a brunette wig. Mike told her what he thought looked best. He wasn’t embarrassed. “The most significant thing was seeing Jade look at herself in the mirror approvingly. You could see she liked the way she looked.”

“My dad was really great,” Jade says simply.

“When one person in the family changes, everyone has to,” Anne says. “But how many parents can show their kids flat out that they love them, not because she’s who we want her to be, because she’s who she is? It’s … an opportunity.”

At home, Jade was one of the lucky ones. But no one was sure how the school would accept her transition.

Northern Secondary, which celebrated its 75th anniversary this spring – a banner with the slogan “Hail, dear old Northern” hangs in the hallway – is described as one of the most diverse schools in Toronto. Though it’s comfortably set in North Toronto, students come from across the city – 400 were refused admission because enrolment was full – for the variety of programs offered. There are 200 courses, catering to gifted students, students with learning disabilities, those with hearing impairment; besides a strong academic program there is also an applied program and a large co-op placement. It was one of the first to have a gay-straight student alliance.

“Sixty-one kids played the final in junior football – they won the city championship,” says principal Bob Milne, who was on a leave when Matt made his transition. “A hundred and fifty kids were playing rugby. They don’t cut the teams. One hundred kids were in the school play. There is a place for everybody. Any kid in this school can start a club – we have a juggling club, a Danny de Vito club, a baseball-card collectors club.”

Though Jade had been on Northern’s track team and was a distance runner, her interests were more solitary – computers and playing the World of Warcraft, a multi-player online game in which players create their own characters. Jade says she’s drawn by the competitive aspect of the game, where characters are perpetually at war. (“I play Alliance and work to eradicate the Horde.”) But it’s one thing to not be a joiner, and quite another to make a radical change that’s bound to set you apart. Jade’s parents were terrified someone would hurt her. The school’s preparations, which took about three months, included consultation with Steve Solomon, the school board social worker, and with Toronto police, who suggested Jade consider alternative routes to school for the first days and carry a cellphone.

A few staff wondered why Matt couldn’t wait until university, why he was exposing himself to danger and potential ridicule. “My response was, ‘Whenever is there a good time?'” Callender says. “She’d waited 17 years, who’s to say she should wait until September?”

Adults understood the safety worries, but they had to learn about the complex world of transgender and how they could support Jade. “It was today’s adults evolving with today’s youth,” Callender says.

After a day or so of thinking it over, acting principal Kerins sent out his letter to the staff. In it, he said Matt was a wonderful and courageous student who has the right to live as he chooses at school and in the community. “Matt will be as smart and funny and nice as before, except he will be dressing differently in order to feel more comfortable. It is our professional duty, as board employees, to support Matt to the best of our abilities.”

Things became routine very quickly. When one sees Jade walk with her classmates, share candies before class, deftly direct a student senate meeting, first impressions of incongruence quickly give way. At Northern, there are students with orange hair, students in wheelchairs, gay students, students wearing absurd clothing. Now, there is also a student who still looks a little like a boy, but feels and dresses like a girl.

Jade admits she felt frightened that first day as she walked through the school. Yet fear was balanced by a new feeling.

“I felt I was just being comfortable for the first time. Moving through the hall, I thought, this is me. I was aware of others. I was very tuned in to placement and what was going on around me. There was some laughter. But no one came up to me directly.

“At the end of the day it was kind of surreal. I never expected anything to happen after years of longing.”

Jade’s position in the school raised certain questions. What part, for instance, should she play in public events? The day after she came out, she made a speech about Festivus, a fictitious alternative holiday on Seinfeld, at the school’s December assembly. She was clearly nervous. “I sat in the audience, near the back,” acting principal Kerins says. “No one said anything where I was sitting. It was something to behold.”

In an interview with the school newspaper, Epigram, Jade answered the questions students may have been too polite to ask: what transgender meant, which washroom she used – a staff washroom – what Jade’s sexual orientation was and would she have a sex change. “It’s a common misconception that gender identity and sexual preference are linked,” she explained. “In reality most transgender people are still attracted to members of the opposite sex.” She criticized the media for consistently portraying transgendering as comedy. “(It) is never shown in a good light.”

At her first Student Administrative Council meeting, she invited questions from the group.

All of which helped her classmates. “With those straight answers from him, her, we could understand what she’s going through and why she made those decisions,” says Jennifer Lovering, a Grade 12 student, sitting outside school with friends after class.

This transparency seemed important. “She didn’t try and hide it. She said, ‘This is what I’m going to do’ – so there was no target,” says Matthew Worts, who, like other students, sometimes spontaneously switches pronouns midstream. “He didn’t remove himself from his group of friends,” he adds. “Everyone thought of her as the same person – she was hanging out with the same people just like she did before, she just changed her look.”

Boys on the football team, throwing a ball outside school on a recent afternoon, may not have understood or particularly liked Jade’s choice, but they defended it. “It was kind of shocking, but you have to allow it,” says Nathaniel Budhoo. “Some guys said, ‘Oh, come on, why?’ but they wouldn’t say anything. They didn’t want him to feel worse. But now, everyone seems fine with it.”

Some do feel the school president should more closely reflect the majority of students at Northern. “I don’t know if he does that,” Jesse Warfield says. “As a student, he has the right to express himself in his own way, but as a representative of the school – maybe some things should have been brought forward in the campaign. I voted for Matt, not Jade.” He adds, in a way that seemed typical of students interviewed: “He was a nice guy and still is.”

A minor effort to have Jade removed from the presidency, impeached, really, didn’t go anywhere. When she spoke at the Grade 8 orientation, there was a bit of laughter in the auditorium, but the older students shot looks at the younger ones and the laughs faded. Kerins says the kids, as much as the adults, set the tone. “Kids are incredible, as long as they feel they are heard. Where you get problems is when you pretend nothing is going on.”

There were compromises. Jade joined her class on a school trip to France, rooming with a male student for the first week in a hotel. But the travel agent couldn’t arrange a family for her to billet with. Jade seemed pleased to just go and – she’s a teenager, after all – to skip out and come home a week early.

Jane Steelemore, chair of the parent council, says she received one phone call about Jade, from a parent asking if the council was going to “address” the issue. “My response was we didn’t have an issue to address.”

Jade’s parents still worry for her safety – “the unusual is always a visible target,” Anne says, “but I don’t worry every moment of the day anymore.” Mostly, she is thankful for the goodness and goodwill that have been extended to Jade. “We live in the best city in the world.” The school has been “perfect,” she says. “There is extraordinary kindness and acceptance in this world, and we often don’t expect it.”

Despite her openness about the minutiae of changing gender, when Jade’s asked what it means to her to feel like a woman, a curtain falls. She yawns, and the animation of earlier conversations – about how much she loves writing, how much fun she has reaching certain levels in Warcraft games – vanishes. “I don’t know how to describe it. I don’t know if anyone can. I just feel more comfortable viewed as a woman. Looking in the mirror, it just feels right.

“Definitely having people treat me as one helps. I think what might be useful is that no one knows why exactly someone becomes transgender and feels the way they do. The cause is unknown. I do know I need to express myself and have the world view me as who I really am.”

She’s content cross-dressing for now, though she hasn’t ruled out the possibility of a sex-change operation. By law she would need to live as a woman for two years before beginning the process.

She says it’s important to know there are many expressions of transgender.

“A lot of people think because you’re transgender, you have to be very femmy…. In the transgender community there’s a wide spectrum, many different people, and some get into looking like Barbie dolls, very, very feminine. Some don’t feel the need to express femininity. It’s more or less how your brain is – it’s not dependent on interests.”

Jade’s classmates, with their open hearts and good intentions, have supported her. They still get their pronouns mixed up and feel embarrassed and sometimes apologize. They worry that she is vulnerable. But, as Ben McNelly says, you take a deep breath and go forward.

“She showed a great level of bravery and trust,” he says. “If she had that trust in me, to tell me those things, the least I can do is be supportive of her. But I can’t deny part of me wants her to be Matt again. We had great times when she was Matt. If she knows deep down she’s female, it won’t impede our friendship, but part of me wants Matt back. I don’t know why that is, perhaps because I’ve known her so long.”

Jade will be leaving home in the fall to go to university in British Columbia. Mike spent some time earlier this month dropping into restaurants and stores on Church St., searching for summer job possibilities for her. It was part of his job as a parent, he thought, to help Jade through the first big hurdle of finding work.

She’s happier with her world. There are far fewer panic attacks – and those were just brought on by the stress of yearlong school projects, she says. She feels comfortable at Northern. “I don’t even think about it. On the street I’m more self-conscious. Sometimes there are rude comments: ‘Queer, fag, f— you.'”

On one recent day, Jade got cat calls. Which she took as a compliment, she says, smiling wryly, “Whatever I did that day worked.”

by Leslie Scrivener

June 26, 2005

Toronto Star