LGBTQIA Safe Sex Guide

Overview

Historically, when sex education was introduced to the general public, content was focused on puberty education for cisgender people, heterosexual sex, pregnancy prevention, and reduction of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). During that time, there was a great deal of stigma and discrimination associated with being lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA). Gender-inclusive terms such as “nonbinary” and “trans” hadn’t yet entered mainstream language and culture.

This historical context and rampant homophobia and transphobia created a foundation where most sex education curricula didn’t acknowledge the existence of LGBTQIA and nonbinary individuals. Sex education programs were, instead, developed based on the assumption that those receiving the information were solely heterosexual and cisgender.

That’s why we partnered with GLSEN and Advocates for Youth to ensure that this safe sex guide is aimed at understanding the nuanced, complex, and diverse gender identities, sexual orientation, attractions, and experiences that exist in our world, which vary across cultures and communities.

Why we need an LGBTQIA-inclusive safer sex guide

Traditional safe sex guides are often structured in a way that presumes everyone’s gender (male/female/nonbinary/trans) is the same as the sex they were assigned at birth (male/female/intersex or differences in sexual development).

Sex education resources often use videos, pictures, and diagrams as a way to convey important information, though these images and videos have historically failed to reflect or provide information about same-sex and queer relationships. In fact, the GLSEN 2015 National School Climate Survey shows that only about 5 percent of LGBTQ students saw LGBTQ representation in health class.

These guides also often unnecessarily gender body parts as being “male parts” and “female parts” and refer to “sex with women” or “sex with men,” excluding those who identify as nonbinary. Many individuals don’t see body parts as having a gender — people have a gender.

And as a result, the notion that a penis is exclusively a male body part and a vulva is exclusively a female body part is inaccurate. By using the word “parts” to talk about genitals and using medical terms for anatomy without attaching a gender to it, we become much more able to effectively discuss safe sex in a way that’s clear and inclusive.

For the purposes of this guide, we’ll refer to the vagina as the “front hole” instead of solely using the medical term “vagina.” This is gender-inclusive language that’s considerate of the fact that some trans people don’t identify with the labels the medical community attaches to their genitals.

For example, some trans and nonbinary-identified people assigned female at birth may enjoy being the receptor of penetrative sex, but experience gender dysphoria when that part of their body is referred to using a word that society and professional communities often associate with femaleness. An alternative that’s becoming increasingly popular in trans and queer communities is front hole.

The lack of representation and anti-LGBTQIA bias that LGBTQIA and nonbinary people often see in safe sex guides stigmatizes certain sexual behaviors and identities. It’s also directly related to the health disparities and higher rates of HIV and STIs reported within these communities.

Discrimination in the sex ed world along with lack of access to healthcare tailored for LGBTQIA people and their needs plays a role in health disparities observed in LBGTQIA communities. For these reasons, it’s imperative for safe sex guides to become more inclusive of LGBTQIA and nonbinary people and their experiences. This will help address barriers to accessing care and effective educational tools, while simultaneously normalizing and acknowledging the true diversity that exists with regard to gender and sexuality.

Gender identity

Gender identity is one component of gender and refers to the internal state of being a male, female, some combination of both, neither, or something else completely. Gender also includes gender expression and gender roles. Gender is different from sex, which is related to biological traits such as chromosomes, organs, and hormones.

While a medical professional attending a birth assigns sex by looking at an infant’s genitals, gender is something each person comes to understand about themselves. It’s important to remember that gender has to do with who someone is, and sexual orientation has to do with who someone is attracted to.

Here’s a list of more common gender identities and a quick description to better understand them:

- Cisgender is the word used to describe someone whose gender identity is the same as the sex that was assigned to them at birth.

- Trans is an umbrella term that often includes anyone who might identify as transgender (a gender identity describing someone who doesn’t exclusively identify with the sex they were assigned at birth), genderqueer, nonbinary, transfeminine, transmasculine, agender, and many more. Sometimes people wonder if trans people are always gay, while other times people assume trans people can’t be gay. Just like cisgender people, individuals who identify as trans can have any sexual orientation — straight, gay, bisexual, queer, lesbian, or asexual. Also, different people use gender identity labels differently, so it’s always good to ask someone what that term means to them in order to get a better understanding.

- Genderqueer is a gender identity used by people who do things that are outside of the norm of their actual or perceived gender. Sometimes this label overlaps with the sexual orientation label.

- Nonbinary is a gender identity label that describes those who don’t identify exclusively as male or female. This means that a nonbinary person can identify as both male and female, partially male, partially female, or neither male nor female. Some nonbinary people identify as trans, while other don’t. If you’re confused which one of these terms to use for someone, as always, just ask!

- Transfeminine is an umbrella term used to describe someone who was assigned male at birth and identifies with femininity. Someone who identifies as transfeminine may also identify as a trans woman or female.

- Transmasculine is a gender identity describing someone who was assigned female at birth but identifies with masculinity. Someone who identifies as transmasculine may also identify as a trans man, trans woman, or male.

- Agender is the word used to describe those who don’t identify with any gender or can’t relate to gender terms or labels at all. Sometimes people assume those who identify as agender also identify as asexual, but this isn’t true. Agender people can have any sexual orientation.

Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation describes someone’s emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction to another person or group of people. Sexual orientation doesn’t tell us anything about the types of sex someone prefers or what body parts someone has. It simply gives us an idea of the range of people someone is attracted to.

Here are some common sexual orientations:

- Heterosexual, also known as straight, is a sexual orientation to describe the physical, emotional, and sexual attraction to people who have a gender that’s different from their own.

- Gay is a sexual orientation to describe a person who’s emotionally, romantically, or sexually attracted to people of their same gender and sometimes used by a person who identifies as man and who is emotionally, romantically, or sexually attracted to other men.

- Lesbian is a sexual orientation to describe a person who identifies as a woman, and who is emotionally, romantically, or sexually attracted to other women.

- Bisexual is a sexual orientation to describe a person who is emotionally, romantically or sexually attracted to two or more genders; often used to mean attraction to people with one’s own gender and other genders.

- Queer is a sexual orientation to describe a person whose feelings of emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction don’t fit into predetermined categories.

- Asexual is a sexual orientation to describe a person who doesn’t experience sexual attraction or desire towards other people but may experience romantic attraction.

- Pansexual is a sexual orientation used to describe a person who’s emotionally, romantically, or sexually attraction to people regardless of their gender or sex.

Consent

Sexual consent is the act of agreeing to participate in any kind of touching or sexual activity. Sexual consent should take place in every sexual encounter and with all types of sexual activity and touching. Yes, even kissing!

Often, consent involves a lot more than just a simple yes or no. It’s important to remember that the absence of a no doesn’t mean yes. There are often multiple behaviors to a sexual interaction, and consenting to one stage doesn’t necessarily mean someone is consenting to everything.

Checking in with your sexual partner before and during sexual behaviors can help create a safe environment where sex can be a mutually pleasurable and positive experience grounded in respect and understanding. If you’re worried about ruining the mood or moment, take time before things get heavy to talk about consent and sex as well as barriers and protections. This strategy allows sexual partners to stay in the moment while also having clarity about what’s OK and what isn’t.

Though consent is a serious thing, it doesn’t have to be a buzzkill. They are lots of ways to provide consent and finding the ones that work for you and your partner(s) can help create the trust and open communication that’s necessary to explore and have fun with sex.

Consent can come in different forms, and it’s important to become educated on the various types in order to decide which form is the best fit for a particular person, group of people, or situation.

- Verbal or expressed consent is the act of using words to confirm agreement that you want something. The main thing to remember about this form of consent is that everything about the agreement is verbalized using words and there are no elements that are assumed or implied. If it wasn’t stated in the conversation or question, it wasn’t consented to.

- Implied consent is conscious and intentional agreement that someone wants something through their actions or body language. This type of consent can be tricky because the way body language and actions are interpreted varies from person to person. For example, one person may view flirtatious body language and touching as implied consent for more touching of other parts of the body, whereas someone else may view it as simply consenting to the flirtation and touching that’s currently happening. For this reason, it’s always best to get verbal consent too. Talk with your partner about how they feel about implied consent and the ways they use their body to communicate consent in a given sexual interaction.

- Enthusiastic consent involves both the verbal act of agreement and communicating the level of desire associated with that agreement. In simplest terms, it’s telling someone what you want and how badly you want it. The idea behind enthusiastic consent is that taking ownership and stating personal needs and desires is an important part of the consent process. Not only does this guide someone in knowing their partner’s wants and desires, both generally and in a given moment, but it also establishes a system of open communication for conveying preferences, turn-ons, and fantasies before and during sex.

- Contractual consent involves creating a written contract that outlines the sexual preferences of the partners involved and clearly states the sexual acts that can and can’t be performed, and in which situations. For some people, contractual consent means consent isn’t needed in the moment. For others, verbal, implied, or enthusiastic consent still need to happen. It’s important to remember that anyone can opt out of the contract or change the terms of the contract at any time. It’s helpful to revisit contractual consents regularly to ensure each person is still on the same page.

Practicing contractual consent allows partners to engage in sexual encounters knowing what’s agreed upon, both in terms of consent and sexual activity. That’s why contractual consent is nice for many partners who prefer not to talk about consent in the midst of sex. This can help people feel more prepared and comfortable, while also eliminating the need to interrupt a passionate moment.

STIs

An STI is an infection that’s passed from one person to another through sexual contact and activity. Although there’s often a lot of negative stigma — and sometimes shame — around contracting STIs, it’s actually quite common. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there are approximately 20 million new STIs contracted every year in the United States, and 50 percent of these cases occur among people aged 15 to 24. Talking about STIs can be scary, but it’s super important to get tested regularly and talk with your healthcare provider about STIs if you’re sexually active.

Testing is also important, because many people with an STI may not know they have one. There are a number of STIs that don’t come with significant or visible symptoms, which is why getting tested is the most effective way to stay STI-free.

There are great websites, such as Get Tested, that’ll help you locate a local testing center. STD Test Express and SH:24 are great resources for those interested in at-home STI kits and testing.

Most STIs can be treated with medication and many are cured with antibiotics. But when risk factors are ignored and STI symptoms go untreated, serious health issues can arise.

Each of those infections falls into a class of either bacterial STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis) or viral STIs (HPV, HIV, herpes, and hepatitis C).

Treatment for a bacterial STI is typically a course of antibiotics. Unlike bacterial STIs, most viral STIs can’t be cured with antibiotics. The only one that can be entirely cured with treatment in most cases is hepatitis C.

When someone becomes a carrier of a viral STI other than hepatitis C, that person remains a carrier of the virus. Medications are used to help decrease the chances of transmission and protect against the serious health issues that could surface if the STI is untreated. But the virus remains inside the body.

Thanks to effective medications and safe sex precautions, most people with viral STIs are able to effectively manage symptoms and reduce their risk for transmitting the infection during sex.

Talking with a healthcare provider about these options and their effectiveness may help someone decide which combination of methods makes the most sense for them.

Previously, there’s been a significant amount of research and data pointing to increased rates of STIs within the LGBTQIA community. More recent studies, however, suggest that flaws in the language, questions, and topics included in past research result in questionable conclusions related to STI disparities and contribute to stigma surrounding the LGBTQIA community.

The language used in research should shift away from using gender and sexual identities to categorize certain sexual activities and experiences and instead focus on the sexual acts and behaviors that present the most risk for transmission and contraction of STIs.

Types of sex and ways to make sex safer

We frequently hear about the importance of paying attention to our physical and mental health. For many people, it’s important to add sexual health to that list. Sexual health is an important part of your overall health. Sexual health includes:

- discovering sexual identity and attractions

- finding ways to communicate them to others

- preventing the transmission of STIs

Having access to information about how to stay safe during sex gives people the comfort and confidence to explore and fulfill their sexual desires with less anxiety and worry. Understanding different types of sex and ways to make it safer is the first step in taking charge of your sexual health.

Safe penetrative sex in a front hole, vagina, or anus

Penetrative sex, also known as intercourse, is the act of inserting a body part or toy inside someone’s front hole, vagina, or anus. It’s important to be aware that the person being penetrated, also known as the receptive partner, or “bottom,” is typically at a higher risk for contracting STIs than the partner who’s penetrating, also known as the inserting partner or “top.”

The risk for transmitting HIV to a bottom during unprotected anal sex is 15 in 1,000 compared with 3 in 10,000 for transmitting HIV from a bottom to a top.

Safe oral sex on a clitoris, front hole, vagina, penis, scrotum, or anus

Oral sex is when someone uses their mouth to stimulate a partner’s genitals or anus.

Safe sex with hands

Fingers and hands can be used during sex to stimulate parts of the body such as the penis, front hole, vagina, mouth, nipples, or anus.

Safe sex with toys

One way to have sex with yourself and with partners is by using toys such as vibrators (can be used on the front hole and vagina), dildos (can be used on the front hole, vagina, and anus), plugs (can be used anally), and beads (can be used anally). These toys can help stimulate body parts both internally and externally.

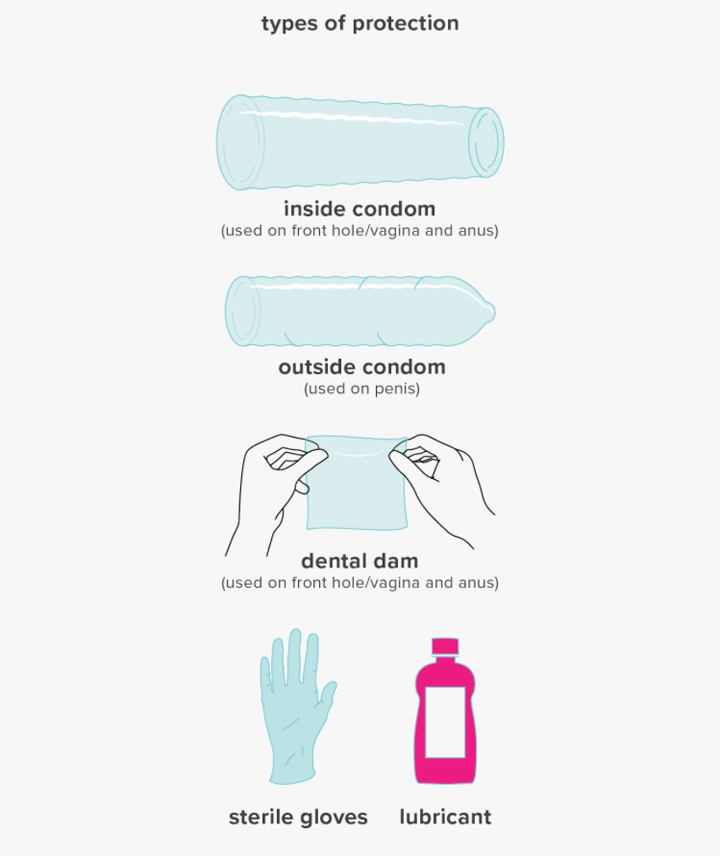

Methods of protection

Knowing how to properly protect yourself is key to both safe sex and staying in good sexual health. There are a number of different types of sexual protection barriers, including:

- outside condoms

- inside condoms

- dams

- gloves

- lube

Water-based lubes are always best with latex condoms. This is because they reduce the chance that the lubricant will break down the barrier and reduce its effectiveness.

These methods of protection can and should be used for all kinds of sex, which means everything from touching genitals to penetrative sex. Using barriers during sex helps reduce the risk of getting or giving STIs to sex partners, providing peace of mind that can make sex more fun and pleasurable for everyone. Barriers should also be used with sex toys, if sharing between two or more persons.

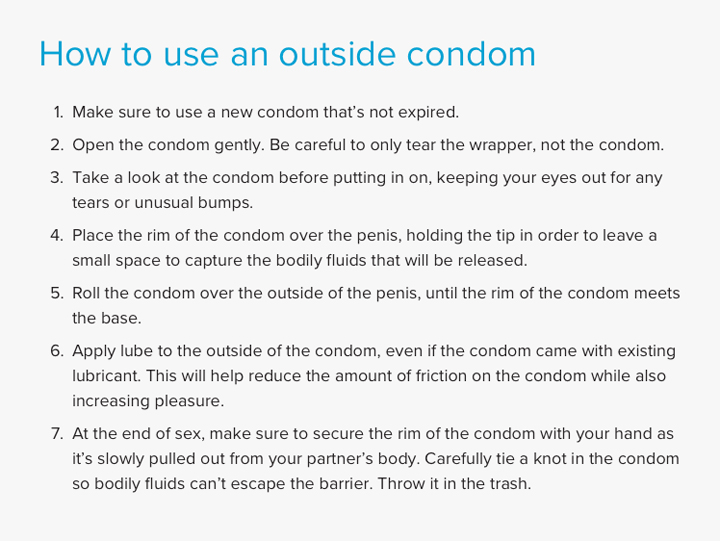

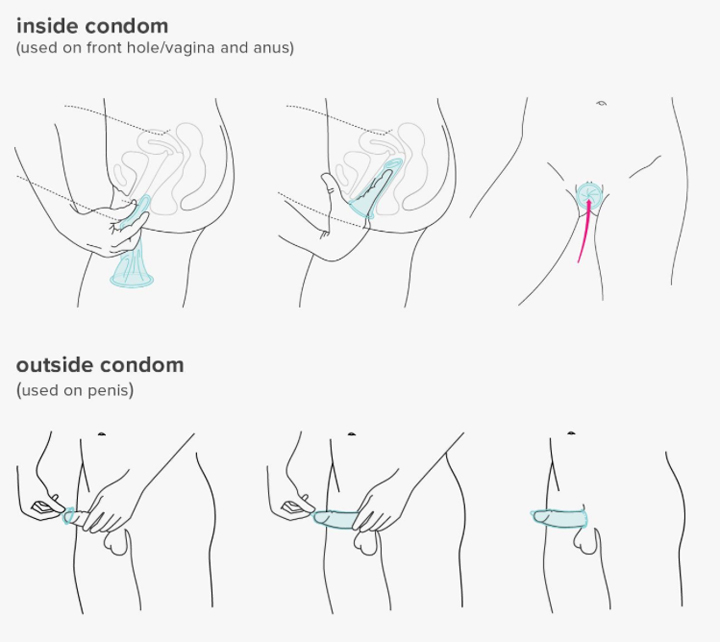

In order to get the most out of sexual protection barriers, they need to be used correctly and for the appropriate sexual activity. Here’s a step-by-step guide for using some of the most common barriers:

Outside condoms (commonly referred to as ‘male condoms’)

An outside condom is a sexual protection barrier that can be used for penetrative and oral sex involving a penis. Outside condoms are designed to contain the bodily fluids (such as semen or ejaculate) that are released during sex. This prevents sexual partner(s) from being exposed to anyone’s fluids but their own.

Outside condoms can be purchased at convenience stores, grocery stores, and drugstores. They can be purchased at any age and are often free at many health centers and STI testing clinics.

For those with a latex allergy, use a non-latex condom made with polyisoprene or polyurethane.

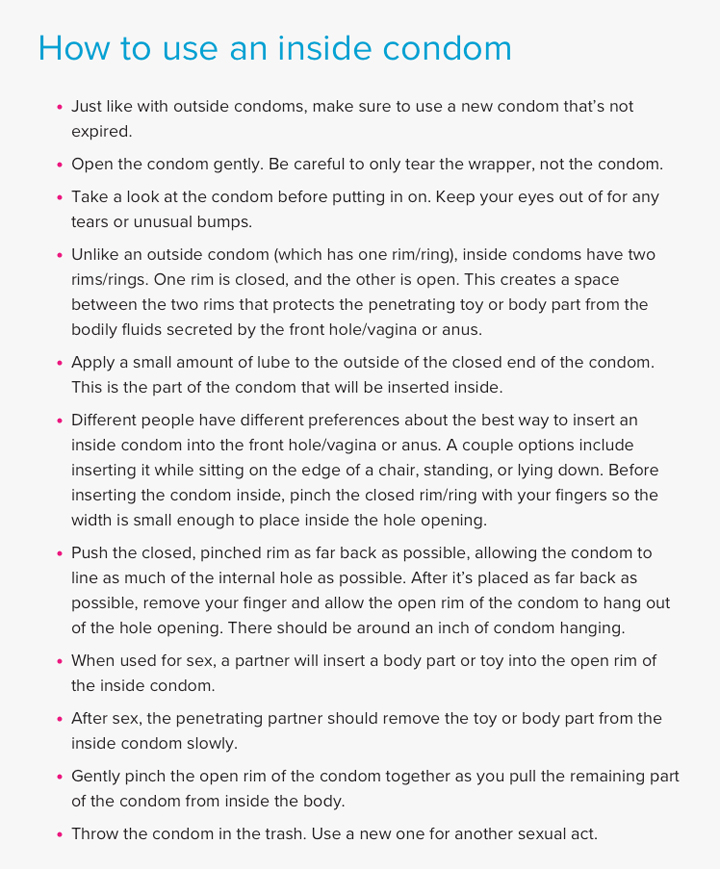

Inside condoms (commonly referred to as ‘female condoms’)

An inside condom is a sexual protection barrier that can be used for penetrative sex involving a front hole/vagina or anus.

Inside condoms are designed to line the wall of the front hole/vagina or anus in order to prevent bodily fluids from coming into contact with the toy or body part penetrating it. Inside condoms are often harder to find than outside condoms.

Only one brand is available in the United States, but health clinics often have them. They’re also available by prescription.

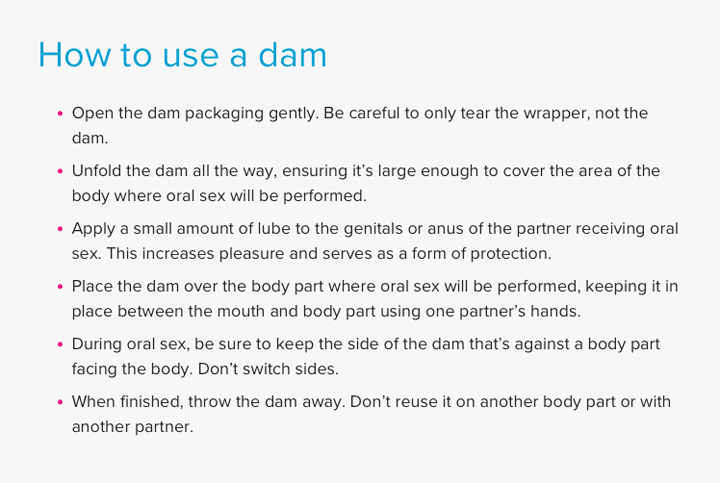

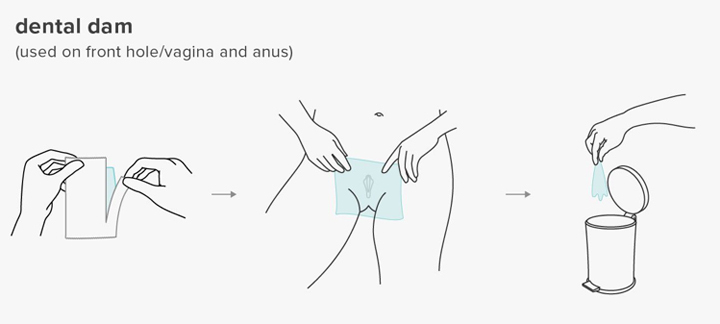

Dams (also known as dental dams)

A dam is a sexual protection barrier used during oral sex to help decrease the risk of contracting or transmitting an STI, such as gonorrhea, HPV, or herpes.

Dams can be used with lots of different body parts, including a front hole/vagina, clitoris, and anus. Even though oral sex involving a penis has a higher risk of STI transmission, it’s important to know that oral sex involving other body parts still presents risks.

Dams can be harder to find in stores than outside condoms. You can create your own dam by cutting open an outside condom and using it as a barrier between body parts. Check out this step-by-step guide to get you started.

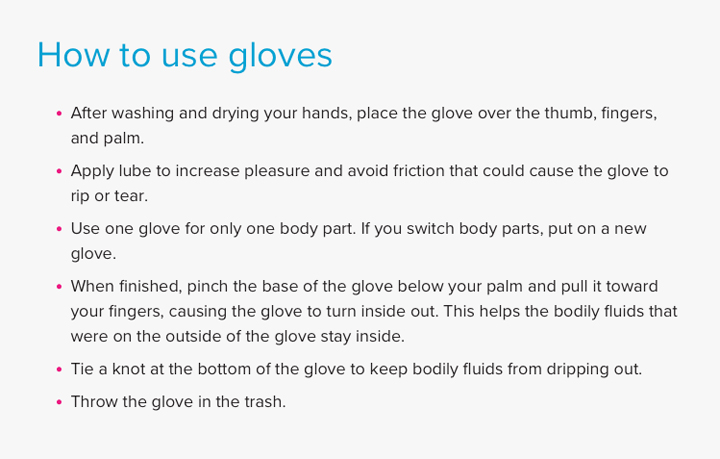

Gloves

Gloves are a great way to prevent the risk of infection when having sex with hands and fingers. They protect genitals from the germs found on hands and also keep hands safe from the bodily fluids that the genitals and anus release during sexual activity. Gloves can also provide a smooth texture that often increases pleasure during sex with hands.

Lube

Lube by itself isn’t the most effective sexual protection method, but it can still act as a protective factor during sex. This is because it prevents excessive friction from occurring, which can break down condoms and cause small tears in the genital area.

If using a latex barrier with lube, you’ll want to make sure to use lube that’s safe for latex. Non-water-based lubes can break down latex, causing the latex barrier to become less effective. Water-based lubes, however, are always a good choice. They can be used on latex, toys, and body parts. When the correct lube is used, it can both enhance pleasure and add an extra element of protection.

Using lube is easy! Just apply it to a barrier or body part as needed to prevent friction, cuts, and tearing. If used for oral sex, make sure it is an edible lube.

Protection for trans bodies

Body parts and genitals vary in shape, size, color, and texture among all humans. Trans people use the same methods cisgender people use to engage in safer sex: outside condoms, inside condoms, gloves, and dams. Some trans and nonbinary-identified people choose to use gender-affirming interventions, such as hormones and surgery, to change their body to align with who they are. There are other trans-identified people who don’t feel the need to change their bodies to feel alignment and congruence around gender. There are also many who would like to but can’t due to other factors, such as finances, medical reasons, and legal issues (depending on where in the world they live).

For those who are able to and choose to pursue gender-affirming interventions (and for their partners), it’s important to have access to information about how those changes impact pleasure, sexual functioning, sexual health, and risk of STI transmission.

As mentioned before, there’s no gender or sexual identity that automatically places someone at more of a risk for STI infections. It’s the sexual behaviors someone engages in — not how they identify — that make them more or less at risk.

Each person is responsible for doing their part to understand their most appropriate forms of protection for their body. This only leads to safer and more fun sex for them and their partner(s).

Preventive care

Self

Staying informed about your STI status and overall sexual health is an important goal. In order to maintain good sexual health, it’s important for people to know their own body and pay attention to it.

Finding a healthcare provider who’s the right match can be another key factor in sexual health and wellness. Establishing care with a healthcare provider who’s the right fit creates space for open communication between patient and provider and can make regular checkups for general overall health more appealing.

Likewise, if someone is sexually active, STI testing should be a regular occurrence. It’s also important to know that there are at-home STI tests and other types of testing centers that allow people to get tested without seeing a doctor. In the United States, minors who are 12 years old or over can seek out sexual health and STI testing without a parent’s permission. Many of the clinics serving youth and young adults offer a sliding scale, so people can pay what they can afford.

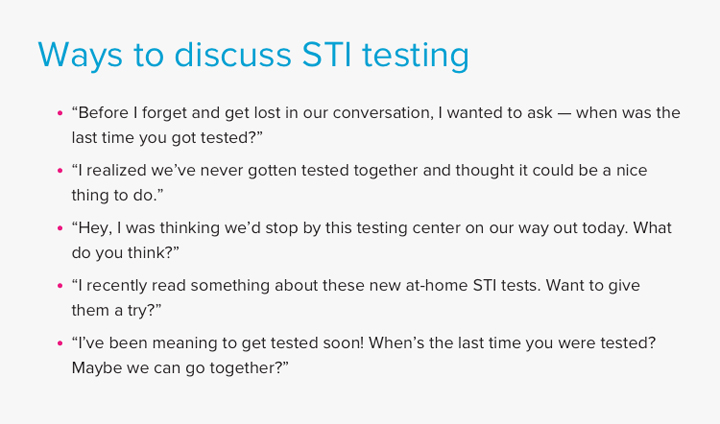

Partners

Talking about STIs with a partner(s) isn’t always easy or comfortable, but it’s an important thing to practice. Going to get tested with a partner is a great way to open up the conversation about STIs while also staying informed about your own status. Doing it together can foster trust, vulnerability, and confidence — three things that also lend themselves to great sex!

Knowing your status and your partners’ STI status will also provide important guidance around the sexual protection barriers, medications, or combination of both that will keep everyone safest.

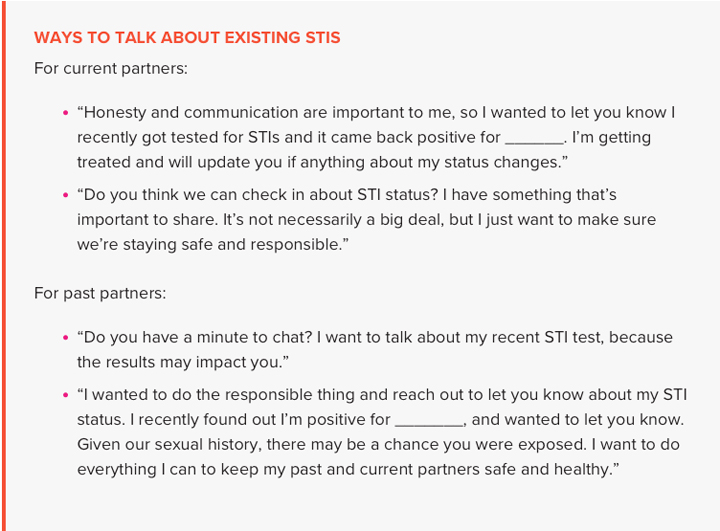

Testing positive

It can be hard to talk about testing positive for an STI. It’s important, however, to remember that contracting an STI is much more common than people might think. The shame and embarrassment many feel around testing positive stem from the fact that there’s not enough openness and conversation about how common it is.

When someone tests positive, it becomes their responsibility to share this status with past partners who may have been exposed and current partners who could be exposed. That said, the person sharing the news shouldn’t be made to feel badly about their status. For many who have had an STI in the past, they took medication, no longer have it, and therefore can’t transmit it.

For others, they might have an STI with chronic symptoms they need to manage in an ongoing way. Open, honest, nonjudgmental communication will lead to better sex. Plus, there are tons of ways to stay safe even if someone has an existing STI.

Each person deserves access to information and services that affirm and support their sexual and gender identity while also caring for their overall sexual health. The right educational tools for the community and training for medical providers and mental health professionals can ensure LGBTQIA communities are better equipped to understand how to protect themselves and how to practice safer sex.

Practicing safer sex and protecting yourself won’t only increase the chances you and your sex partners stay STI-free. It’s also a tangible way to practice self-care and self-love.

Mere Abrams, MSW, ASW, is a gender specialist, researcher, educator, and consultant in the San Francisco Bay Area, providing gender-affirming services to trans, nonbinary, and gender-expansive children, teens, and young adults. As a clinical researcher at the UCSF Child and Adolescent Gender Center, Mere works on the first National Institutes of Health-sponsored research, studying long-term medical and mental health outcomes for trans youth starting puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones. Mere was a contributor and editor of “The Transgender Teen: A Handbook for Parents and Professionals Supporting Transgender and Non-Binary Teens” and speaks publicly on the topics of ethical considerations for working with trans youth and their families, nonbinary experiences, and gender diversity and inclusion.

This article is reprinted from the Original at Healthline with permission and gratitude! Aug 20, 2018