Attorney and Plaintiff in the First Same Sex Marriage Lawsuit of the Modern Gay Rights Movement

by Craig Dean

Perhaps no topic stirs the imagination as the legalization of same-sex marriage. In this veritable minefield of tradition versus progress, twenty years ago attorney Craig Dean filed the first discrimination suit to legalize same-sex marriage in over forty years when his marriage license application to his partner was denied by the District of Columbia because both parties were men.

Since then he has been speaking out on issues affecting gay and lesbian couples and has become a powerful advocate for legalization of gay marriages. His presentation gives a historical background to same-sex marriage, places it in the context of society and the modern gay civil rights movement, and discusses what the future may hold.

Craig is currently the Executive Director of the Equal Marriage Rights Fund, and President of Outright Speakers & Talent Bureau. He also does motivational presentations on “Coming Out” and “Living with Pride” utilizing his own life experience to illustrate the benefits of living with equality, dignity, and respect. As well, he has developed a presentation specifically geared to training professional college staff members on gay and lesbian issues.

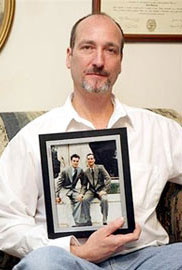

Marriage Equality Pioneer Craig Dean Wants First D.C. Marriage

In 1993 Craig Dean, together with his late boyfriend Patrick Gill, sued the city of Washington D.C. for denying them a marriage license:

Craig Dean’s first wedding was attended by thousands, and as he recited his vows, gay couples behind him on Constitution Avenue echoed their own.

It was 1993, and Mr. Dean and boyfriend Patrick Gill headlined what was billed as the largest gay marriage ceremony at the time. Mr. Dean, then 29, and Gill, 26, were celebrities after suing the District of Columbia for denying them a marriage license. They were on CNN, were profiled in The Washington Post and sat on Oprah’s couch.

And though they lost their landmark case, the city last month finally did what it had refused to do back then: legalize gay marriage.

Mr. Dean, who now lives in South Carolina and runs a talent agency for gay and lesbian speakers, said he cried when he read the news.

“They owe me a marriage license,” he said.

The law still has to survive a review by Congress, which has final say over the District’s laws. Lawmakers appear unlikely to intervene, though, so gay couples could be marrying in Washington — legally this time — by March. It would be the sixth jurisdiction in the country where gay marriages are allowed. And Mr. Dean, who carries bittersweet memories of his and Gill’s pioneering effort, wants the first spot in line.

Mr. Dean and Gill were not practiced advocates when they applied for a marriage license in November 1990. Mr. Dean had just graduated from Georgetown University’s law school. Gill worked in the men’s accessories department of Macy’s, selling pens and umbrellas.

But Mr. Dean was “young and brash and ambitious and forthright,” said their lawyer, William Eskridge Jr., and Gill, though less publicly confident, was “charming” and a “babe.” They made for a model case, Mr. Eskridge said.

“It was really the first lawsuit of this new era,” said Mr. Eskridge, a Georgetown law professor at the time who now teaches at Yale University.

Just filing for the marriage license made many established gay groups angry. Some thought the pair was asking for too much and feared a backlash. Lambda Legal Defense Fund Executive Director Tom Stoddard called their challenge “shortsighted.” Washington was “probably the worst jurisdiction in the country” to try to legalize same-sex marriage, said Mr. Stoddard, an influential advocate who died of AIDS in 1997. Let other places do it first, he urged, then come back to the city.

Mr. Dean didn’t back down, drawing motivation from the time Gill was rushed to the hospital and Mr. Dean hurried to the emergency room, only to be told he couldn’t see his partner. If they were married, things would be different, Mr. Dean thought. So he researched the city’s laws and was convinced nothing in the code prevented them from getting married.

The lawsuit went on five years. Ultimately, a three-judge panel of the D.C. Court of Appeals ruled against the pair. District laws were never intended to let gay couples marry, wrote Judge John Ferren, who still sits on the court.

His colleague, Judge John Terry, also a sitting justice, was more blunt: “They are, of course, free to refer to their relationship by whatever name they wish. But it is not a marriage, and calling it a marriage will not make it one.”

For Mr. Dean, the defeat was personal. He said he believes the pressure of the case also affected the health of his boyfriend, who had AIDS.

“He was really holding on in the hopes that we would win,” Mr. Dean said.

Gill died in June 1997, just over two years after the decision.

“Whether it became legal or not, he was my husband,” Mr. Dean said. “If anything, it was a marriage in the way we lived our lives.”

In Mr. Dean’s garage sit five boxes with typed briefs, notes and letters from the case. A marriage rights banner he helped carry in marches in San Francisco and Washington is in his attic.

His current partner, photographer John Blevins, told him not to cry when the District passed its law last month; he should be proud. Mr. Blevins and Mr. Dean met several months ago on a blind date, but their romance has moved fast. On Christmas, Mr. Blevins put a ring in Mr. Dean’s stocking and asked, “Would you do the honor of marrying me?”

“Yes,” Mr. Dean said, as long as he gets a real Washington wedding.

And he has a message for the marriage bureau: “The first name on the list should be the one who is waiting 20 years.”